AFTERWORD

In recent years, the development of media has transformed how we experience moving images. Stuck in an endless loop of image production and consumption, images haunt us, invade us and produce us. In this post-cinematic regime, our inherited cultural identities, established forms of subjectivity and embodied sensibilities are constantly reshaped.

Sets and Scenarios explores our heightened proximity to images and what it means to live under their influence. The programme was originally devised to occupy Nottingham Contemporary’s private and public spaces with sculptural installations, sound works, video and live performances by Adam Christensen, Eva Gold, Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi, and Aaron Ratajczyk, evolving over the course of an afternoon and evening. Conceived around a mobile viewer, the visitor would enter a series of different atmospheric environments. Central to the project was experimenting with the ephemerality of the encounter between viewers and works – liveness – understood in relation to its contingency, resolute to the physical space and the collectivity of the experience. [1] In response to the pandemic lockdown, Sets and Scenarios was reimagined online.

[1] Erika Balsom, “Live and Direct”, ArtForum, Sept. 2014.

From the specificity of the site

to the specificity of the screen

The transition to an online platform asked us to revisit our original enquiries. Sets and Scenarios’ delving into different modes of spectatorship, in the context of the lock down, translated to analysing the ways we look online, our relationship to the screen, and how such relations might influence our habitual perceptual patterns. How do we choreograph different modes of spectatorship within the limitations of the screen? How is liveness to be approached within the context of a website? In the screen, liveness comes to be understood as a feeling, rather than an event happening in real time. [2] It does not derive from the instantaneity of the events, rather it is found in the ways in which these are experienced. Upon entering the website, the viewer experiences the works one after the other, directed through a linear three act structure and interludes. Each of the acts presents a different practice and mode of spectatorship.

For the inaugural week, alongside the commissions is presented a live screening of films and moving image works taking over the website every night, the viewer losing the agency to access the rest of the content, pause or forward.

[2] TARA MCPHERSON, “RELOAD: LIVENESS, MOBILITY AND THE WEB” IN NEW MEDIA, OLD MEDIA: A HISTORY AND THEORY READER.

I was brought up to be a spectator... [3]

Central to our inquiry has been James Richards research into the chaos of quotidian media and psychically haunting images. Two works by the artist are presented in the evening screening — What Weakens the Flesh Is the Flesh Itself (2017) and Not Blacking out Just Turning the Lights off (2012). What Weakens the Flesh Is the Flesh Itself stems from a collaboration with Steve Reinke articulated around the exchange of found media clips. This form of intergenerational communication through images recurs in Deborah Stratman’s Vever (for Barbara) (2019), reviving abandoned film projects of Maya Deren and Barbara Hammer. In What Weakens the Flesh Is the Flesh Itself, James Richards and Steve Reinke repurpose Albrecht Becker’s auto-erotic photo collection showing his extreme body modification, a reflection on the shaping of the self through flesh and images, as well as the arousing, fulfilling and negating of desire.

The chaos of quotidian media and the ways it influences us psychically echoes across Sets and Scenarios’ inaugural screening programme. Cerith Wyn Evans’ Degrees of Blindness (1988) expresses different capacities of seeing through a late 1980s aesthetic collage. Whilst evidencing how perception evolves with media, the work itself is a testimony to an era’s way of seeing. In Degrees of Blindness, the past is channeled through the act of viewing, extending its tentacles via digital, cinematic, and post-cinematic images. This constant haunting of the present by images of yesteryear became central to our reflection on what it means to inhabit the post-cinematic – the moving image and screen becoming a portal for the collapse of eras.

This montage of earlier eras in the present has been noted by Mark Fisher as characteristic of our twenty-first-century culture, and as so prevalent it is no longer noticed. In Ghosts of my Life (2014), Fisher argues the present era is defined by anachronism, where time periods slip into one another, generating, in his words ‘an increasing sense that culture has lost its ability to grasp and articulate the present.’ [4]

Sets and Scenarios proposes this hauntological lens to look at our relationship to images in the context of the post-cinematic era. The haunting of the present by images of the past and future manifests throughout the programme – Mary Helena Clarck’s invokes of the ghosts of cinema; Jacques Derrida and Ken McMullen’s frame cinema as the art of ghost; Shahryar Nashat’s ruminates on the death of images; Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi’s camera becomes tool to seek the ghosts of history, etc.

[3] John Irving, The World According to Garp (Boston, MA: E.P. Dutton, 1978) p.1.

[4] Mark Fischer, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (London: Zero Books, 2014) p.9.

… I was raised to be a voyeur [5]

The act of watching is central to Eva Gold’s commission presented in Act I. In For Your Discreet Viewing Pleasure, Eva reflects on the inherent voyeurism of our spectatorial habits, delving into notions of perversity, agency and control.

In For Your Discreet Viewing Pleasure, Eva Gold devises scenes of obsessive voyeurism through text and fragments of film. The voyeur she crafts mingles with the big screen’s own – presented alongside her writing are repurposed film footage from David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) and Michele Haneke’s Hidden (2005). Both revolve around the threat of being watched, a recurrent subject in the film industry and analysed by academic Norman K. Denzin as indicative of a need for the voyeuristic figure. [6] By invading personal space, the voyeur keeps alive the idea of a private world distinct from the public sphere. [7] In For Your Discreet Viewing Pleasure, privacy is intruded upon repetitively: by the handyman, onl00ker, pest control, bed bugs and us, reading through the protagonists dreams, violating their last thresholds. Another trespasser can be located: film, finding ground in cinematic memory – a recurrent concern of the artist. Here, further than invading the psyche, the moving image transforms how the dreamer looks: their vision fuses with the camera, the naked eye reproducing the mechanical eye – zooming in, shaking. In a similar movement of influence, the dream sequence transforms how the viewer sees the moving images.

In For Your Discreet Viewing Pleasure, film has penetrated the depth of the mind, and together with ceaseless other invasions, attest to the impossibility of a private subconscious. During lockdown, dreams were reported to be increasingly vivid and the domestic space – associated with the psyche – was all that we had. Eva Gold works at the threshold of both; crafting threats of violation highlighting their precarity.

In our post-cinematic present, the multiplication of media facilitates the voyeuristic gaze. Gaining in agency, it finds solace in the digital realm. Eva Gold’s enigmatic onl00ker peeps through a structure made for watching – the live cam show. While onl00ker takes pleasure in looking, they are under our gaze – part of an endless game of both voyeurism and exhibitionism resonating with today’s digital viewing regime and habits.

The voyeuristic vision explored by Eva Gold is persistent and returns in the evening screening. Perv City (Act 1) (2020) commissioned by Parrhesiades, features footage taken by The Perv, their camera zooming in on the lips, neck and eyes of a news presenter. The voyeur’s heavy, lustful breathing and wet mouth noises are audible, soiling the film itself. One night, the footage is screened alongside Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983), a comment on the obsessive gaze usually cast upon women in film. Variety is the story of a female returning the gaze, ‘looking at how the cinema looks at her’. [8] Eva Gold and Bette Gordon both reveal perceptual patterns and how they are shaped by film.

[5] John Irving, The World According to Garp (Boston, MA: E.P. Dutton, 1978) p.1

[6] NORMAN K. DENZIN, THE CINEMATIC SOCIETY: THE VOYEUR’S GAZE (LONDON: SAGE PUBLICATIONS, 1995).

[7] IBID.

[8] BETTE GORDON AND REBECCA LIU, ‘SCREENING FEMALE DESIRE: BETTE GORDON’S “VARIETY” 35 YEARS ON’, ANOTHER GAZE, 13 FEBRUARY 2019, AVAILABLE AT HTTPS://WWW.ANOTHERGAZE.COM/SCREENING-FEMALE-DESIRE-BETTE-GORDONS-VARIETY-35-YEARS/ (ACCESSED 29 MAY 2020).

Rehearsing

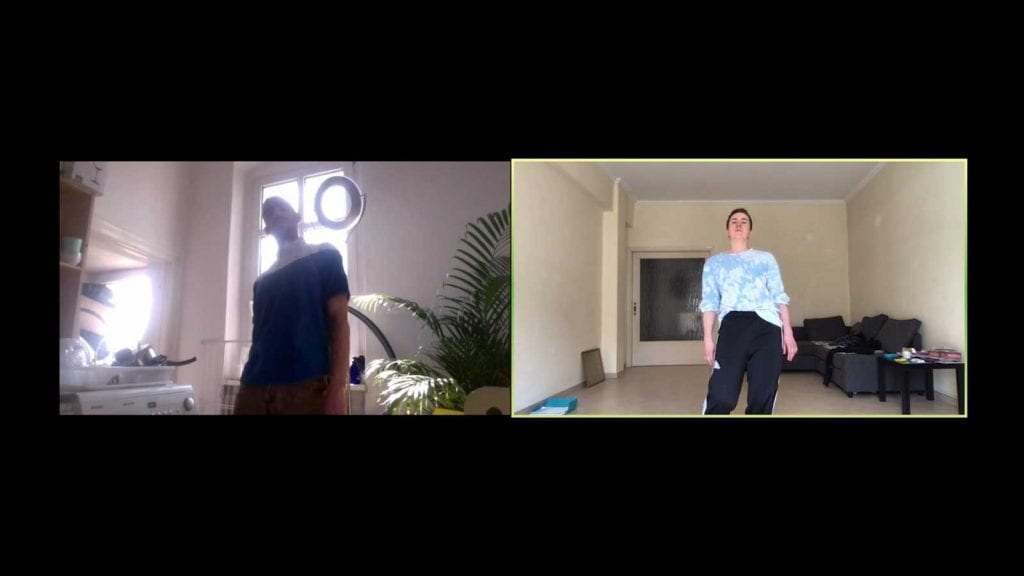

The act of looking also presides in Aaron Ratajczyk’s collaborative practice. For Sets and Scenarios, Aaron proposes to rehearse alongside one of his friends based in Berlin, Juan Pablo Cámara, using a video call device. The screen serves as a window for performers to look at each other. In these one-to-one rehearsal video calls, images are replacing and extending physical presence. While the work was developed before the COVID-19 pandemic, it became all the more poignant in times of national lockdowns. What are the alternatives when performance loses its direct confrontation between the performers’ sweat, breath, exhaustion and the viewers’ gaze?

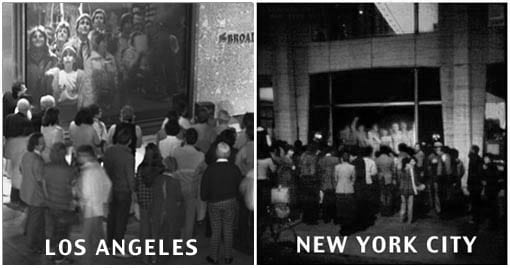

The dialogical format of A Hole in Space ATH-BER 01 explores the possibility of new forms of social relations through the Internet and technology, a concept that has been explored as early as the 1970s. The title A Hole in the Space refers to Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz’s 1977 pioneering work, consisting of live performances via video-conference by using NASA satellites. Unsuspecting people walking on the streets of New York see their images superimposed on screens, together with those walking on the streets of Los Angeles. For Rabinowitz, the performance was similar to an electronic version of a dance studio mirror, an exercise during which the performer looks at his reflection to develop a choreography. [9]

Aaron Ratajczyk creates a similar exercise: the performers mirror each other with synchronised movements intertwining their bodies within the digital space. Alongside the images, we can hear the artists commenting on this exercise: ‘I see in you the result of my movements.’ The screen’s use becomes ambiguous, at the same time window and mirror. Within this game of looks, the audience’s gaze comes in as an anonymous witness of this fusional rehearsal– an exercise usually not intended to be public – observing them within their private homes. We become almost Eva Gold’s voyeur.

On the website, Aaron Ratajczyk’s work is presented as interludes. Originally, interludes are short musical or theatrical compositions inserted between parts of a larger composition. By focusing on immediacy and bodily gestures, the rehearsals break the linearity of the different scenarios presented in each act. The interludes’ interruptive and transitional qualities resonate with Aaron’s performance, acting as a resistance to the logic of the spectacle and narration of this programme.

In the face of reduced mobility, Aaron Ratajczyk’s work proposes to escape within the poetics of the in-between. His exercises and body movements situate themselves between immediacy and mediation, remoteness and proximity, connectedness and isolation.

[9] Kris Paulsen, Here/There: Telepresence, Touch, and Art at the Interface (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017) p. 116.

To recount

In Võ An Khánh’s black and white photograph The Mobile Military Medical Clinic 9/1970 an injured soldier is carried through a makeshift hospital in a swamp during the American occupation in Vietnam. We could almost believe that this field shot was staged because of its cinematic composition, the stillness of the protagonists and its surreal setting. The image is one of many that inhabit Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi’s imaginary map, presented in Act II, where viewers are offered the possibility to explore different landscapes of history, biography and memory through ‘portals’. The multiple movements through time and space presented in these portals, allow the viewer to follow similar movements that are embedded within the artist’s working process.

The hallucinatory and multi-layered films Synchrisis, Movement II and On Your Pale Blue Eyes dive deep into our unconsciousness to dissolve the seemingly polar opposite constructions of collective memory and personal history in a world governed by mass media. Shots of empty cinema theatres and close-ups of eyes remind us of our own condition of spectators. We listen to the artist’s father recounting his traumatic experience of witnessing Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation. At the same time, we see the image of Elisabet Vogler’s reaction to the TV footage of a monk burning himself to death taken from the film Persona of Ingmar Bergman. The power of images within the construction of collective memory echoes Jacques Derrida’s reflections in the film Ghost Dance (1983) presented as part of the screening programme. Unlike the general belief that the notion of ghost belongs to ancient tradition, Derrida asserts that ‘… the development of modern technologies of images, of cinematography and telecommunication enhances the power of ghosts and their ability to haunt us.’ How to draw the limit between witnessing and voyeurism when images present the violence and exploitation endured by marginalised subjects?

When invaded by ghosts of images, what is the best way to mourn the past? In Syncrisis, movement II, Han proposes alternative methods of transmission, her voice melodiously covering her father’s as he recalls his move from Vietnam to Germany during the Cold War. She values dialogue as the multiple letters of close artists and writers inserted within the map can attest.

The making of an image

In Death by Mystery, Adam Christensen invites us to his house-cum-theatrical-stage, a recorded performance where the distinction between on- and off-set is unclear. A series of scenes unfold throughout the course of an evening as Adam moves through different atmospheric environments – from the intimacy of his own bedroom to a cooking scene in his kitchen, passing by a highly dramatic scene in the baroque makeshift stage of his studio and collective moments of gathering with friends on the hallucinatory landscape of his rooftop. At times intimate, confessional and melancholic, at others funny and overly dramatic, the 33-minute-long performance for the camera takes the viewer on a journey of different emotions.

It is hard to categorise Death by Mystery: is it a concert film? Documentation of a performance? A moving image work? Or none of the above? When performing live, Adam can be thought of as a character in a Werner Schroeter film, having just stepped outside the screen, where his dramatic figure, vivid storytelling and strong stage presence facilitate an immersive and intimate experience for those present. For the first time, in response to the limitations imposed by the lockdown, he steps inside the screen and gives a performance directly to the camera, inviting viewers to enter his domestic environment while he enters theirs.

Devised in three acts, written on the day of its filming and shot in one go, we see the artist making and unmaking himself as he changes outfits in between the different scenes. Adam produces images like he himself has been produced by them. At some point, while singing, we see Klaus Kinski in a fighting scene from Zulawski’s The Most Important Thing is Love playing on one of the monitors. Brigitte Neilsen, Jeanne Moreau and Melina Mercouri, also do cameos at different points throughout the programme. Three movie stars completely different to one another, yet all influential to and reflective of Madam – Adam’s alter ego. Distinctions between self and image, proximity and distance, reality and fiction become malleable throughout this work.

This ambitious ad-hoc presentation is achieved with the help of Adam’s friends and the community of artists he lives with – we see them both in front of the camera and behind it. Although the work is not experienced at the moment of its filming, having it play automatically as one enters the third act of the programme, hearing it before seeing it, with no option to fast forward, makes one feel as if they themselves have entered inside Adam’s room and have been invited to spend 33 minutes with him. When asked about the difference of performing for the camera rather than for an audience the artist responded: ‘It’s just a different way of thinking about entertainment.’

Continuum

The third act links back to the first via an interlude. This loop effect recurs in another form on the closing day. Sets and Scenarios’ inaugural week daily screenings ends with a closing stream featuring all moving image works presented over the course of the week. The looping structure and continuous feed, in closeness to the endless production and consumption of images forming our online viewing habits, stages a collapse of past and future into a durational present.

Further to collapsing time, the inaugural week screenings collapse moving images source and definition. Low and high resolution, poor and rich image, glitches and scratches, early 2010 CGI imagery, 16mm film, user phones camera picture co-exist, flattened by the viewer’s computer screen. The different media reflect the images’ motion with technological change, carrying with them the promises it held – as many lost futures flickering.

We became accustomed to the many different textures of the works as the skin of the film. [10] This notion of skin, as well as flesh and body of the image traversed our inquiry, evidencing an embodied relationship between viewer and screen and between viewer and image. This contact – of the skin of the image to our own skin – is deeply personal, shaping our post-cinematic selves, our subjectivities. Moving images, registered on the retina, do not come to rest.

* We do not own the copyright for these images. This is for non-profit educational purposes.

[10] Jennifer M. Barker, The Tactile Eye, Touch and the Cinematic Experience, (Berkeley, Los Angeles, CA, London: University of California Press, 2009)

Interviews

Adam Christensen

Eva Gold

Could you describe a formative encounter with moving images?

In the film Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984), when Travis and Jane are talking through the one way mirror, in that peep show sort of place. Ever since I first saw that film I haven’t been able to get it out of my head, those two scenes in particular. There’s so much sadness in it but it’s so beautiful… and there’s something else, a feeling that I’ve never been able to put my finger on.

Then when I was at Goldsmiths, I was taught by Mark Fisher for two years. During that time I began to look at film differently, a lot closer. I was searching for something quite particular – that feeling from Paris, Texas that I couldn’t articulate. I couldn’t really explain what it was but he got it without me having to. He was a very astute teacher and incredibly knowledgeable, so he would give me all these lists of titles to watch. I saw so many films in that time which ended up informing my studio practice later on.

What is it about neo-noir films that you find interesting?

There’s so much in the genre it’s hard to know where to start – the city landscape, the lighting, the characters… there’s an ambiguity that’s really compelling, some other motivations that aren’t ever explained, something darker going on outside the frame, more psychological. It breaks from the formality of the noirs of the 1940s and 1950s, which are so stylised and can sometimes feel a bit clean. But the neo-noir feels dirtier, seedier, more colourful and chaotic.

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi

Could you describe a formative encounter with moving images?

It’s hard to pin it down to one formative encounter with moving images. It’s more like strata of formative encounters. All these encounters bleed into each other and the formation takes place in the interstices. Some of the layers in these strata are:

Hu Bo, An Elephant Sitting Still, 2018, film still, courtesy of Hu Bo, Dongchun Films

Mati Diop, Atlantics, 2019, film still, courtesy of Mati Diop, Cinekap, Frakas Productions, Les Films du Bal

Robert Bresson, Au Hasard Balthazar, 1966, film still, courtesy of Robert Bresson, Argos Films, Athos Films, Parc Film, Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Abbas Kiarostami, Close-Up, 1990, film still, courtesy of Abbas Kiarostami, Kanoon

Alice Rohrwacher, Happy As Lazzaro, 2018, film still, courtesy of Alice Rohrwacher, Amka Films Productions, Ad Vitam Production, Pola Pandora Filmproduktions, Tempesta

Ingmar Bergman, Persona, 1966, film still, courtesy of Ingmar Bergman, AB Svensk Filmindustri

Joshua Oppenheimer, The Act Of Killing, 2012, film still, courtesy of Joshua Oppenheimer, Final Cut for Real

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tropical Malady, 2004, film still, courtesy of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kick The Machine

Pedro Costa, Vitalina Varela, 2019, film still, courtesy of Pedro Costa, Optec, Sociedade Óptica Técnica

What affects your sense of history?

Events in the present and imaginations of the future affect my sense of history…

Five years ago, I went to the cinema to see Christopher Nolan’s science fiction film Interstellar with my mother, who shockingly had a post-traumatic experience while watching it. The protagonist’s interplanetary odyssey in search of a habitable planet, necessitated by an impending apocalypse on Earth, reminded her psychologically and physically of her own history: her journey from Vietnam to Thailand and then to Germany, as she escaped from the communist regime.

An imagination of the future experienced in the present makes the past emerge. In these moments time dissolves. History is not something distant in the past, not something disconnected from who you are, from who I am in the present. My mother made the difficult decision to leave Vietnam in 1979, as she was no longer able to endure the pressure and structural violence that the new regime exerted on her as a woman, as a Southern Vietnamese, and as a half Chinese. It is because of this decision and the personal/political conditions shaping this decision in 1979 that I am here in Germany in 2020. Maybe this is why I am interested in working with the moving image as a tool to explore the entanglements between my mother and I; between the world and myself; between different identities, questions, events, conflicts, histories, times, spaces – and eventually to make time and space collapse and create a relation to infinity.

Another aspect that concerns me is the possibility to redefine histories through the moving image. Growing up, I watched a lot of films about the war in Vietnam, mostly American films, which shaped my perception of Vietnamese history. Back then I didn’t have the critical thinking tools to question what I see but now I ask myself: is the Vietnamese experience equally represented as the American experience of this war in cinema? Whose interest does it serve? Do American-produced films about the War in Vietnam serve American interests and, by extension, contribute to the sustentation of American hegemony?

‘My film is not a movie. My film is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam. It is what it was really like,’ [1] states Francis Ford Coppola, when speaking about his film Apocalypse Now at the Cannes Film Festival. I am highly critical towards such a statement made by an American white man who has no direct experience of this war and yet claims to portray a truthful depiction of it without the inclusion of other voices.

In the novel The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen criticises Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in one whole chapter: ‘[The filmmaker’s] arrogance marked something new in the world, for this was the first war where the losers would write history instead of the victors, courtesy of the most efficient propaganda machine ever created. […] In this forthcoming Hollywood trompe l’oeil, all the Vietnamese of any side would come out poorly, herded into the roles of the poor, the innocent, the evil, or the corrupt. Our fate was not to be merely mute; we were to be struck dumb.’[2] The embodiment of American imperialism in Apocalypse Now is also addressed by Jean Baudrillard from the angle of Coppola’s film-making methods: ‘Coppola makes his film like the Americans made war […] with the same immoderation, the same excess of means, the same monstrous candor […] Coppola does nothing but that: test cinema’s power of intervention, test the impact of a cinema that has become an immeasurable machinery of special effects. In this sense, his film is really the extension of the war through other means, the pinnacle of this failed war, and its apotheosis. The war became film, the film becomes war.’ [3]

The problems addressed by Nguyen and Baudrillard can be found in both classic and recent films about the war in Vietnam. Furthermore, this problem not only concerns (hi)stories of the past, but also of the present: While working as an assistant on a Canadian documentary about climate change in Vietnam, a Vietnamese friend of mine was deeply disturbed by how the director imposed a preconceived narrative about the consequences of climate change on the landscape as well as the people, whose lives and realities are completely disconnected from this very narrative. But through the manipulation of certain words, actions, conditions and ways of filming, this skewed narrative was brought into existence in order to fit the director’s world-view.

I am aware of my position as someone conditioned in Germany/Europe and who, although a child of a boat refugee, doesn’t have first-hand experience of being geographically displaced by political forces.

So as an outsider dealing with Vietnamese hxstory in my work, I aspire to practise deep listening and self-criticality during my research and artistic process in order to avoid reproducing the very same problems addressed above in my own work. [4] How do I consciously de/construct the memories and histories of someone else through the lens of my subjective experience? How can I learn to ‘not speak about’ but instead ‘just speak nearby’ [5] or speak with the other, while developing a position of critical intimacy? [6] How can I practise disobedience towards hegemonic perspectives of history? And how can I replace the imperial gaze with one that is sensitive to the historical complexity and specificity of each individual human being and context?

And beyond the problem of representation, I believe the question is: how do we (re)imagine reality? For the act of creating images is not only a form of representing reality but also imagining, inventing, sculpting, transforming reality. How does the reality we create affect us and others? Is it destructive or constructive?

We create images, images create us. Histories shape us, we shape histories.

A cinematographer holds a camera filming itself in the mirror.

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi, Linger On Your Pale Blue Eyes, 2016, film still, courtesy of the artist

[1] FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA, ”HEARTS OF DARKNESS: A FILMMAKER’S APOCALYPSE (1991),” THRIFT VHS, MAY 16, 2016,

VIDEO, 02:57, HTTPS://WWW.YOUTUBE.COM/WATCH?V=LXOWB5IQRUI.

[2] VIET THANH NGUYEN, THE SYMPATHIZER (NEW YORK: GROVE PRESS, 2015), 176.

[3] JEAN BAUDRILLARD, SIMULACRA AND SIMULATION (ANN ARBOR: THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS, 1994), 59-60.

[4] I am interested in the practice of self-criticality as embodied by Jean-Luc Godard in his contribution to the collective film Loin du Vietnam (1967). Having applied for a filming permit in order in Vietnam, Godard was rejected by the authorities in Hanoi. In Camera Eye, his contribution to Loin du Vietnam, Godard reflects on this rejection: “I think they were right, because I could have done things more damaging than beneficial. […] I think these ideas were falsely noble and it seems difficult to make things. I mean talk about bombs, when they don’t fall on your head and you speak in the abstract.” In Camera Eye we see Jean-Luc Godard operating a camera, while questioning his relationship with the subject of his film, the American War in Vietnam. Performing a monologue, Godard creates a cinematic space, in which he critically examines his own reality as a filmmaker in France in relation to the reality of the War in Vietnam, American imperialism, the French working class, and other political movements in the world.

[5]Trinh T. Minh-Ha cited in Schneider, Arnd and Christopher Wright, eds., Anthropology And Art Practice (London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2013), 47.

[6] “That’s what de-construction is about, right? It’s not just destruction. It’s also construction. It’s critical intimacy, not critical distance. So you actually speak from inside. That’s deconstruction. My teacher Paul de Man once said to another very great critic, Fredric Jameson, “Fred, you can only deconstruct what you love.” Because you are doing it from the inside, with real intimacy. You’re kind of turning it around. It’s that kind of critique.” Citation from “Critical Intimacy: An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,” Los Angeles Review of Books, accessed October 12, 2019, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/critical-intimacy-interview-gayatri-chakravorty-spivak/.

Screening notes

TUESDAY 16 JUNE, 8PM

Shahryar Nashat, Image is an Orphan, 2017, 18 min. One hour loop.

In Image is an Orphan, images are given a flesh of zero and one. An image speaks, its robotic voice sharing existential reflections on the origins, life, death and afterlife of images: “How will I die? Who will carry me? Who will feel my after-effects?” Shahryar Nashat borrows and manipulates material from two online accounts sharing viral videos of fails, falls, pranks, and other, capturing moments of loss of control of the body and failure.

WEDNESDAY 17 JUNE, 8PM

Correspondances — Intergenerational dialogues through images

Deborah Stratman, Vever (for Barbara), 2019, 12 min.

A cross-generational binding of three filmmakers seeking alternative possibilities to power structures they are inherently part of. The film grew out of abandoned film projects of Maya Deren and Barbara Hammer. Shot at the furthest point of a motorcycle trip Hammer took to Guatemala in 1975, and laced through with Deren’s reflections of failure, encounter and initiation in 1950s Haiti. A vever is a symbolic drawing used in Haitian Voodoo to invoke a Loa, or god.

James Richards and Steve Reinke, What Weakens the Flesh is the Flesh Itself, 2017, 40 min.

What Weakens The Flesh Is The Flesh Itself is a video made with Steve Reinke, an artist and writer with whom Richards has collaborated since 2009. The starting point for the work is a series of photographs and collages found amongst the private archive of Albrecht Becker – a production designer, photographer and actor imprisoned by the Nazis for being homosexual – held at The Schwules Museum, Berlin. Amongst the portraits of friends, work-related images and photographs taken whilst serving in World War II, is a collection of self-portraits that reveal an obsessive commitment to his personal body modification and to his own image: duplicated, quadruplicated, repeated and reworked within. The artists have drawn on hundreds of these self-portraits and combined them with medical footage, educational film and text to construct a piece that interrogates what it means to build a body of work of the body, and for the body to become a work itself.

Commissioned by Wales in Venice for the 57th Venice Biennale

THURSDAY 18 JUNE, 8PM

Eye contact — on seeing, remembering and what lies between

Ken McMullen, Ghost Dance, 1983, 5 min. (excerpt)

Ghost Dance is a free-form experimental film by Ken McMullen exploring the complex notions of ghosts, memory and past within our modern world. In this extract, Pascal Ogier asks French philosopher Jacques Derrida, playing his own role, if he believes in ghosts.

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi, Syncrisis, movement I, 2018-ongoing, 7 min.

Syncrisis is a multi-layered cinematic libretto in six movements. In movement I, being on the beach at night alone, a woman wonders, if I peer at the darkness with a torch, will I see more than darkness?

Mary Helena Clark, Orpheus (outtakes), 2013, 6 min.

Orpheus (outtakes) is a fake artefact: an outtake of Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950). Shot on high contrast black and white film and photogram, the work brings the viewer in a guessing game, an attempt to identify a spectral presence.

Cerith Wyn Evans, Degrees of Blindness, 1988, 19 min.

In Degrees of Blindness, Cerith Wyn Evans expresses different capacities of seeing through a late 1980s aesthetic collage. The notion of vision and perception is entangled with the evolution of media – Degrees of Blindness itself capturing the late 1980s technological promise and way of seeing.

FRIDAY 19 JUNE, 8PM

The lustful look — the voyeur gazes at her and she gazes back

Eva Gold, Perv City (Act 1), 2020, 30 sec.

Perv City (Act 1) is the first act of a project by Eva Gold titled Perv City commissioned by Parrhesiades, London presented online, in a flat, and at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London. In Act 1, Eva invites viewers to adopt the gaze of an obsessive voyeur, their heavy breathing audible. The protagonist films a news reporter from up close, focussing on her lips, neck, and eyes. The texture of the image —filmed with a 1980s handheld camera— and the sound —loud breathing and wet sounds of tongue and lips moving— stains the film itself with perverse lust.

Bette Gordon, Variety, 1983, 01:40:00 min.

Variety is Bette Gordon’s first feature film. Now a cult classic, the neo-noir movie touches on female desire and pornography based on a script by Kathy Acker, starring New York underground legends Nan Goldin and Cookie Mueller. It follows Christine, the lead female character as she starts her job as ticket officer for a porno cinema theatre in grimy 1980s New York City. Whilst working there, she discovers her sexuality. Christine develops a fetish for voyeurism and embarks the viewers in her newly discovered kink. In an interview, Gordon states Variety sees Christine as a woman daring to look at the way cinema looks at her, prompting the audience to question its own participation in the structure of looking at women in cinema and beyond.

SATURDAY 20 JUNE, 8PM

Inner states — a trip into artificially induced states of being; violating the threshold of the skin, moving images penetrate the depth of the body

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Seroquel, 2014, 8 min.

Voiced by Lydia Lunch, Seroquel® consists of clips from psychopharmaceutical videos played out by EVA v3.0. The work considers the psychoactive effect of psychopharmaceuticals as a technology “that allows capitalism to enter into our relationship to ourselves.” It connects the commodity status of the pharmaceutical industry with that of the digital pornography industry, thus literally allowing capitalism to live and manifest within our minds.

Made by freelance 3D designer Nikola Dechev, EVA v3.0 is a royalty-free product sold online by TurboSquid, a company that supplies stock 3D models for computer games and adult entertainment. EVA v3.0 features as a central character and object of research in several of Meineche Hansen’s works, which explore the overlap between subjects in real life and objects in virtual reality, focusing on their accumulation by capital through the gender binary.

Adam Christensen, The Last Fucking Rave, 2015, 12 min.

The Last Fucking Rave is an account of possession by a demon, the end of a rave, and the demolition of London’s buildings and with it, its counterculture.

James Richards, Not Blacking Out Just Turning the Lights Off, 2012, 16 min.

Not Blacking Out Just Turning the Lights Off delves into alternate states of being through an assemblage of images sourced from the Internet, James Richards personal archive and DVD footage. The work evolves from sensual to violent proposals, evocative of our exposure and consumption of moving images and technology.

SUNDAY 21 JUNE, 12PM

Closing

All moving image works presented throughout the week will be streamed together in a day-long stream that will mark the end of Sets and Scenarios‘ live programme.

Contributors

Adam Christensen is a London-based artist whose practice is realised through performance, moving image, textile, music and installation. Adam’s performances are based on his immediate experiences, coloured by the theatricality of the everyday, the spectacle of domesticity, chance encounters and emotional and physical dramas. Adam has previously exhibited at Overgaden Institute of Contemporary Art, Copenhagen; Baltic Triennial 13, Vilnius, Tallinn and Riga; Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; and Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London. He also performs with music project Ectopia.

Aaron Ratajczyk is a London- and Berlin-based artist whose working practice is realised through moving image, text and performance. He graduated with a BA in Dance, Context, Choreography at HZT / University of the Arts Berlin and is currently completing an MFA in Fine Arts at Goldsmiths College, London. Aaron’s performances have been presented at the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw; KEM, Warsaw; Yvonne Lambert, Berlin; Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam; NDC, Bucharest; Veem House for Performance, Amsterdam; and Import Projects, Berlin, among other venues.

Cerith Wyn Evans lives and works in London. His solo shows include White Cube Bermondsey, London (2020), Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan (2019), Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, O-Town House, Los Angeles, National Museum Wales, UK, Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo (2018). Recent group shows include Marian Goodman Gallery, London, Josey, Norwich, 14th Fellbach Triennial, Germany, Tristan Hoare Gallery, London, Punta Della Dogana, Venice, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo (2019). White Cube, London, White Cube, Hong Kong, Museum of Modern Art, Frankfurt, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, Hayward Gallery, London, Taka Ishii Gallery, 500 Capp Street Foundation, San Francisco, YARMONICS, Great Yarmouth, Palais d’lena, Paris, Hepworth Wakefield, West Yorkshire (2018).

Simon Starling lives and works in Copenhagen. Since emerging from the Glasgow art scene in the early 1990s, Starling has established himself as one of the leading artists of his generation, working in a wide variety of media (film, installation, photography) to interrogate the histories of art and design, scientific discoveries and global economic and ecological issues, among other subjects. He represented Scotland at the 50th Biennale di Venezia (2003), and won the Turner Prize 2005 for his work Shedboatshed. Starling’s work has been presented at the Villa Arson, Nice; the Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel; Mass MOCA, North Adams; Tate Britain, London; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart; and MUMA in Melbourne.

Deborah Stratman is a Chicago-based artist and film-maker who explores landscapes and systems. Her body of work spans multiple media, including drawing, audio, photography and public sculpture. Much of her work points to the relationships between physical environments and the very human struggles for power and control. Stratman was the subject of a mid-career retrospective, The Things Unnamed, at MoMA New York in 2013. She has exhibited internationally including the Whitney Biennial, MoMA NY, the Pompidou, Hammer Museum, Witte de With, Walker Art Center, Yerba Buena Center, and has done site-specific projects with the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Temporary Services, Mercer Union (Toronto), Blaffer Gallery (Houston), Klondike Institute of Art & Culture (Yukon) and Ballroom Gallery (Marfa).

Eva Gold is a London-based artist who works across sculpture, installation, video and writing, often combined in a process of fragmented storytelling. Eva Gold navigates feelings of desire and disgust, and their uncomfortable proximity. Locating a space in which these two meet, she identifies the emotional threshold where arousal tips over into horror. Eva’s practice raises questions about desire in public and private domains, agency, vulnerability, and consent. Eva Gold graduated from Goldsmiths College in 2016 and the Royal Academy Schools in 2019. She recently completed a commission for Parrhesiades, part of which was presented at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London.

Steve Reinke is an artist and writer best known for his videos. His work is screened widely and is in several collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Pompidou (Paris), and the National Gallery (Ottawa). His tapes typically have diaristic or collage formats, and his autobiographical voice-overs share his desires and pop culture appraisals with endearing wit.

James Richards is a Berlin-based artist whose work is concerned with the interaction of the body within a space and generates meaning through abundance and allusion. Richards’ works actively dissuade viewers from passively watching his collaged film works and often consist of ambient installations. Richards’ works have been presented at the 12th Biennale de Lyon, the 55th Venice Biennale, Tate Modern, Performa 2011, CCA in Kitakyushu, and the ICA in London and New York and was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2014. He also received the Jarman Award in 2012.

Juan Pablo Cámara is an Argentinian choreographer and performer who graduated from the School for New Dance Development, Amsterdam, in 2017. His work has been presented in a variety of cities, including Buenos Aires, Amsterdam, Berlin, Vienna, Madrid and Lisbon. Juan Pablo has performed with choreographers such as Jefta van Dinther, Michele Rizzo, Adam Linder and Kat Valastur.

Mary Helena Clark makes films and videos in which she explores narrative figures of speech, the materiality of film and the painting technique trompe l’oeil. She aims to make trance-like, transparent films. Clark’s work has been screened at International Film Festival Rotterdam, New York Film Festival, Wexner Art Center and the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Minh Nguyen is a writer and curator of exhibitions and programmes currently living in Chicago, IL, by way of Saigon, Vietnam. She graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a Master’s degree in Modern and Contemporary Art History. She has organised exhibitions at Chicago Cultural Center (forthcoming), Wing Luke Museum, King Street Station, and SOIL Gallery, and is currently Curatorial Assistant at Conversations at the Edge (CATE), which is a series of screenings, talks, and performances by new media artists. Minh Nguyen’s writing has appeared in ArtAsiaPacific, Art in America,

Art Practical, and AQNB, among others.

Pujan Karambeigi is editorial contributor at Jacobin, co-founder of the criticism newspaper Downtown Critic and a doctoral candidate at Columbia University, New York, where he focuses on cultures of labour and economies of identity. His writing has appeared in Art in America,

Artforum, Texte zur Kunst,

Frieze, Mousse, among others platforms. Most recently, he edited Alice Creischer, In the Stomach of the Predators: Writings and Collaborations

(saxpublishers, 2019).

Shahryar Nashat is an artist who lives and works in Los Angeles. He makes sculptures, videos, and other works in which the human body and its representations play a central role. Desire, mortality, fragility, and resilience are among the thematic concerns his work addresses. Shahryar pays special attention to framing and pedestals, treating them as integral parts of his work. His solo exhibitions include 54th Venice Biennale (2011); Shahryar Nashat: Start Begging, SMK, Copenhagen (2019); Force Life, MoMA, New York (2020). Group exhibitions include Mario Merz Prize, Mario Merz Foundation, Turin (2017); Stories of Almost Everyone, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2018); Searching the Sky for Rain, Sculpture Center, New York (2019); Honestly Speaking: The Word, the Body and the Internet, Auckland Art Gallery, Aotearoa (2020).

Sidsel Meineche Hansen lives and works in London. Her solo exhibitions include LIVE LIFE WELL®, Center for Contemporary Arts, Prague (2019); Welcome to End-Used City, Chisenhale Gallery, London (2019); An Artist’s Guide to Stop Being An Artist, 60K, CoSenhagen (2019); Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2018); End-user, Kunsthal Aarhus (2018). Group exhibitions include The Assembled Human, Museum Folkwang, Essen (2019); Mud Muses, a Rant about Technology, Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2019); The Body Electric, Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis (2019).

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi is a Berlin- and London-based artist whose practice mutates in and out of sculpture, installation, moving image and interdisciplinary research. Her work explores imaginations of freedom at the intersection of film-making and film theory, critical refugee studies and postcolonial studies, personal/prosthetic memory and individual/collective histories. In September 2020, Thuy-Han will begin pursuing PhD research in film at the University of Westminster. She has previously exhibited and screened her work at Atletika, Vilnius; Centro di Musica Contemporanea di Milano, Milan; Gene Siskel Film Center, Chicago; Kunstverein Nürnberg, Nürnberg; Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt; Portikus, Frankfurt; Sàn Art, Saigon; University of Bonn, Bonn, among other venues.

Studio Ghazaal Vojdani is a Design and Art Direction practice, creating close and ongoing work relationships with cultural and educational institutions, independent galleries, editors, curators, designers, and artists internationally, and is further a platform for collaborations of any scale. Ghazaal Vojdani acquired her BA (Hons) from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London (2010), and her MFA from Yale University School of Art (2013), both in Graphic Design. The studio is currently based in Paris (FR) after being established in New York (US).

Vu Tran was born in Saigon, Vietnam, and raised in the United States. He is a fiction writer, a criticism columnist for the Virginia Quarterly Review, and a professor at the University of Chicago, where he directs the undergraduate programme in creative writing. Vu Tran’s first novel, Dragonfish, was labeled a ‘notable book’ in the New York Times and received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

We are truly thankful to all the artists involved in the project, especially to Adam Christensen, Eva Gold, Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi and Aaron Ratajczyk for allowing their work and our relationships with them to develop through the recent constraints of the Covid-19 pandemic.

To our tutors Kelly Large and Amanprit Sandhu, Royal College of Art and Nicole Yip, Chief Curator and Acting Head of Public Programmes & Research at Nottingham Contemporary for their constant guidance throughout.

A special thanks to Andy Batson, James Brouwer, Ryan Kearney, Sofia Lemos, Philippa Sharpe, Wingshan Smith, Sam Thorne, Laura-Jade Vaughan and all the staff at Nottingham Contemporary.

Finally to all those who are part of the programme of Royal College of Art, class of 2020, Curating Contemporary Art.

Website by An Endless Supply

Copyright notice

Please note that the intellectual property rights in all content comprising or contained within this website address (URL) is owned by Sets and Scenarios, Royal College of Art and other copyright owners as specified. All artworks presented on this website are copyright of the Artists.

© Sets and Scenarios, Royal College of Art and the Artists, 2020. All rights reserved.

Accuracy of information

We make every effort to ensure that the content of the site is accurate and up to date, but we accept no liability in relation to typographical errors or third-party information. Although we attempt to link only to appropriate organisations, we cannot accept responsibility for the content of any external website.

Privacy

Sets and Scenarios only uses strictly necessary cookies that enable this website to function correctly. These cookies do not collect personal and statistical data or track users. You can find out more about cookies here. By visiting https://setsandscenarios.rca.ac.uk/ you agree that we can place these types of cookies on your device.